“The designers will not change the world alone” – an interview with Julia Sulikowska

We spoke to Julia Sulikowska, a designer, an author of the Urban Coolspot Project, awarded the 1st place in the make me! competition at this year’s Łódź Design Festival, about designers’ responsibility for the climate, her views on design and the differences in the approach to public space in Poland and Germany.

Bartłomiej Jankowski: Hi Julia! First of all – I would like to talk about you and your design work. Did you always know you wanted to be a designer?

Julia Sulikowska: Not at all! At first I thought I would study architecture. Then I was faced with a choice – architecture at UDK in Berlin or design at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. At that point, for very practical reasons, I decided: “I’m staying in Warsaw”.

BJ: Where did the idea to get involved in urban design come from?

JS: Already during my studies at the Academy of Fine Arts, I directed my attention towards urban issues in many of my design projects. I remember that when I was applying to the Academy of Fine Arts, the theme of the portfolio was ‘the greeting item”. As I found out later, this theme was interpreted very differently by my fellow students. I was inspired by the culture of Podlasie – the benches that stand in front of houses and serve as the focal point of the villagers’ afternoon meetings.. In my project I tried to transfer these traditions to urban reality. This was my first urban project. It was thanks to it that I got into design

BJ: What was this project about?

JS: I imagined that such a solution would be suitable to be implemented in more intimate neighbourhoods with terraced and single-family housing. The buildings are arranged along the street and each plot is separated by a fence – much like in Podlasie. What is missing, however, is some sign in the space to facilitate contact with the neighbours. Such a bench could become a meeting place in cities as well and have a positive impact on neighbourly acquaintances.

BJ: Now I thought of the Hansens’ house in Szumin. They have also put up a bench like this there, to get a bit closer to the local community.

JS: Yes!

BJ: So you already knew that you wanted to deal with design in an urban context?

JS: Yes, I did. The lack of spatial order in Polish cities had struck me for a long time, and to this day I’ve been looking for an answer to the question of what it is due to – why is the approach in the perception and shaping public space, for example in Germany, so different from what we know in Poland?

BJ: You have been living in Berlin for three years now – you obtained your Master’s degree in Product Design at the Kunsthochschule Weißensee there. You are currently working in an urban design studio. The difference you mentioned can be experienced every day on different levels. Can you tell me more about it

JS: There are probably many differences. One of them is the belief that common space belongs to everyone and should be taken care of. A good example is my neighbour in the block who takes care of the garden located in the inner courtyard. She regularly waters the plants and plants new ones. She also doesn’t fence this space off for herself because she does it for everyone. Caring for urban greenery is a common practice here. Many collective social initiatives are also being developed. For example, during periods of extreme heat, people organise themselves and water trees growing next to the streets. This is different from the prevailing approach in Poland of the separation from the common property. This also confirms Filip Springer’s accurate formulation that in our country the common space is rather perceived as a no-man’s land.

BJ: Do you have a thesis as to why this is the case?

JS: Referring further to Filip Springer’s text, I think that apart from the impact of the years of communism on people’s approach to public space, a significant problem is – firstly – the lack of awareness of who is responsible for urban space, and secondly – the lack of widespread art education that would sensitise us to the aesthetics of the environment in which we live. In addition, I feel that specialists in architecture and design do not enjoy much authority. Many Poles feel that their own taste is superior to the knowledge and skills of experts and the context of a place. Due to a lack of collective thinking, we witness a chaos of forms and colours. The welfare of the community is not a priority in Poland. This can also be experienced at different stages of education, not only art education. At school or university, one works individually, and the emphasis is on “me” and “my project”.

BJ: I understand that this also better reflects the reality of the job market? The designers usually have to work in teams….

JS: “Have to” is too much to say, but from what I observe it is seen as a value.

Urban Coolspot Project, design: Julia Sulikowska / from designer’s archive

Urban Coolspot Project, design: Julia Sulikowska / from designer’s archive

Urban Coolspot Project, design: Julia Sulikowska / from designer’s archive

BJ: Let us return for a moment to the attitude of Poles to common space. Let’s assume that we would like this to change. Who could coordinate these changes? Cities and districts, local government organisations? What role could the designers play in this process?

JS: This is a very interesting question! Based on my observations of how it works in Berlin, I believe that city and district authorities play a key role. If these institutions promote and financially support urban and social initiatives, a market is created for designers who can offer their commercial services in this area. There are many different urban design offices in Berlin, thanks to the fact that the demand from the municipal authorities is high enough to enable profitable business activity This is a win-win for everyone, as the closer co-operation between designers, officials and residents results in numerous projects that significantly improve the quality of space.

BJ: Maybe this is a bit off topic… Do you think there are architectural spaces in the city that are more or less conducive to such grassroots activities? I imagine that if you live, for example, in an intimate three-storey block of flats with space for greenery, you perceive the common space a little differently than if you live in apartment blocks like in Gocław in Warsaw’ or in Gropiusstadt in Berlin.

JS: In my opinion, there are many factors that have impact on the intensity of grassroots activities. The nature of the development, the amount of urban greenery in the area and the economic status of the residents play a leading role. In low development intensity areas, for example in villa districts characterised by high residential wealth, fewer community initiatives are created. This is due to the greater economic capacity of individuals. The situation is completely different in densely built-up districts with a lack of urban greenery. In such neighbourhoods, individual residents have no chance to impact the status quo by acting individually. As a group they are powerful enough to initiate a change. In such a situation, the scale of these actions will also be large enough to make a noticeable difference. In conclusion, in some types of urban spaces, residents individually regulate the quality of their surroundings, while in others a coordinated collective action is needed.

BJ: The project you submitted to make me! and for which you were awarded the first place is an urban project. Let’s talk about it. I know that this was the subject of your master’s thesis at the Kunsthochschule Berlin Weißensee.

JS: Shortly before my master’s degree, I worked on a project that dealt with climate analysis and recommendations for local adaptation ideas for a designated area of Berlin. Then I became more interested in the topic of climate change in the context of urban infrastructure. My attention was drawn to the problem of how grey infrastructure disrupts the water cycle in the environment. During rainfalls water is discharged through many channels and disappears into the sewer system as quickly as possible. The result is reduced evaporation during hot, dry days. This contributes to the urban heat island phenomenon, i.e. prolonged overheating of cities during the summer months.

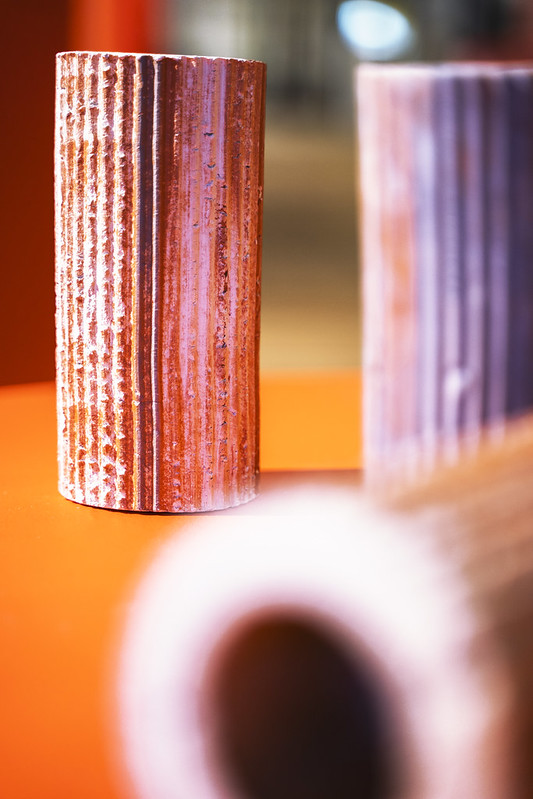

The Urban Coolspot project is a system for retaining rainwater and reusing it for evaporative cooling. The system makes use of porous clay modules, rainwater that we can collect in various manners thanks to the urban infrastructure and air circulation through which evaporation takes place. The aim is to improve the microclimate at the scale of a square or courtyard to ensure thermal comfort for city dwellers during the summer months. The project is also intended to serve as inspiration for how resources such as rainwater, wind, and plants that we have at hand and which are temporarily being wasted, can be used to improve the status quo.

BJ: For me, this project is also a kind of statement – it speaks about your view of design, about you as a designer. You referred to social issues, to the climate crisis and the challenges it presents. The design would be made of clay, using the natural properties of water, and the wind.

JS: Also on a daily basis I try to think about the consequences of my consumer choices. It’s extremely difficult to know whether, by buying a product, we are inadvertently contributing to global problems such as excessive waste production, carbon emissions or human exploitation. When creating the Urban Coolspot, I thought about transparency – using only natural resources and processes. I couldn’t imagine a design project that is geared towards preventing the effects of climate change being powered by electricity or using materials that are responsible for polluting our planet.

BJ: So should contemporary designers take on such a “responsibility for the climate”’?

JS: In one interview I was asked: “Will designers change the world? They will not change it alone. Nor can all “’responsibility for the climate” be attributed to them. Still, they have the skills to show how to meet many challenges. Designers address the problems faced by the society and come up with inspiring solutions.

Urban Coolspot Project, design: Julia Sulikowska / from designer’s archive

Urban Coolspot Project, design: Julia Sulikowska / from designer’s archive

BJ: In addition to wanting to use clay, you also referred to a technology known in antiquity.

JS: Yes, I did: I was inspired by traditional evaporative cooling systems. Ancient Egyptians used clay vases filled with water, which were fanned to increase air circulation and thus the evaporative effect. The second inspiration was a detail from Middle Eastern architecture – a ceramic vessel with water placed in a window opening, roofed so that the water does not heat up. The air that enters the room is cooled down in contact with the cold water, and the warm air escapes upwards through the openwork canopy to the outside. It’s a very simple system that makes clever use of naturally occurring phenomena, water, and the porosity of clay. Nature is our greatest resource. We should think about it when designing cities.

BJ: Have you already had the opportunity to test your design in reality?

JS: Unfortunately, I haven’t. So far I have managed to develop the project in theoretical terms and in the form of small models. With the help of my colleagues, I plan to create and test the first prototype in 1:1 scale in urban space. Based on it, I will be able to check, among others, how strong the capillary and cooling action is, as well as the stability and safety.

BJ: How have you benefited from make me! ?

JS: First of all, it has given me motivation! There is interest in the project, which drives me to develop the idea further. As I have already mentioned, AG.URBAN, a Berlin-based design company where I am employed is interested in the Urban Coolspot Project. The project has been published as one of fifteen ideas for local climate adaptation for one of Berlin’s districts. In addition, I am also in contact with Paradyż, the company that is a patron of the festival.

BJ: And why did you enrol for make me! competition?

JS: I had a feeling that my master’s thesis might be my last chance to take part in this competition. Paradoxically, I was convinced that nothing would come of it, that my design did not quite match the profile of make me! – it was more of a concept than a polished prototype. In the end – to my satisfaction, but also to my surprise – the jury decided that I had won.

Text: Bartłomiej Jankowski, OKK! PR

JULIA SULIKOWSKA

A graduate of the Faculty of Design at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. She received a scholarship to continue her education in Germany and completed her Master’s degree at the Weißensee Art School in Berlin. Professionally, she designs in the context of urban space. She works at the Berlin Urban Design Office, where she is responsible for designing 2D and 3D products, small exhibitions and co-creating urban participatory events. One of her projects, which consisted in creating a climate analysis for a selected Berlin district and proposing local adaptation measures in relation to intensifying climatic conditions, inspired the “Urban Coolspot” project.

See project: Urban Coolspot Project